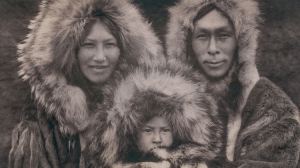

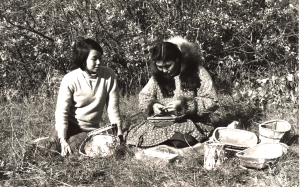

Swift Water Place (2014) is a biographical documentary about archaeologist Douglas Anderson of Brown University, and his lifelong research at Igliqtiqsiugvigruaq, an Iñupiaq site on the Kobuk River in Northwestern Alaska. Anderson’s research focuses on trade economics and has contributed to establishing a continuous narrative of human occupation in the arctic circle extending back at least 10 000 years. The 200 year old settlement site of Igliqtiqsiugvigruaq – an intriguing network of huts and tunnels – was to be the final excavation of Anderson’s career, but it was unexpectedly brought to a halt when human remains were discovered buried within the settlement. This standstill is the crux of the film: will Anderson be able to complete his research and achieve his lifelong goals, or not? It’s a very frustrating climax because as a plot device it feels somewhat contrived, especially when the resolution comes very quickly (especially after such a long set up), when it’s revealed that the local Iñupiaq leaders of the Kiana Traditional Council appear to already have a long and positive history with Anderson (there are also Iñupiaq members of the archaeology team), and so they give the go ahead for the excavation to resume as they too have questions that the scientific research can answer. Conflict resolved, the end.

Swift Water Place could have been better unpacked for a more powerful and meaningful story (and here the website makes up for some of the gaps in the film). The film dances around but never quite pins down the source of the tension, which is National Park Policy not local politics. This is not simply another story about conflict and resolution between archaeologists and Native American communities, but rather the values of a local remote community vs national bureaucracy, with archaeology and archaeologists caught in the middle. What I discovered on the website, and somehow missed when watching the film, was that this particular decision by the Kiana Traditional Council not only allowed Anderson’s excavation to continue, but re-wrote National Park Policy. Now that’s something I would have liked to know more about, but the wider impact of this shift in terms of heritage policy and Indigenous rights is not really addressed by the film. Instead the film ends with further eulogising of Anderson though a partly reconstructed scene of him explaining to Iñupiaq teenagers at school about how proud they should be of their ancestors ability to survive the harsh arctic conditions (this is not a spoiler – it’s in the trailers too).

It’s not easy making a film about the political context of archaeology, especially from a post-colonial perspective. Filmmakers and participants must always be strategic in what they say and how, lest they taint the water for the next collaborative excavation, film or (most importantly) for community wellbeing. Also, at 27 minutes one gets the impression this film was restricted to a half-hour length, which perhaps is not long enough to do the full story justice (there’s a lot of material to cover here). What I suspect is the case in Swift Water Place, is that Anderson really is held in high regard by the Iñupiaq community – I mean, he’s been working with them for over 50 years and judging by the interviews with Iñupiaq elders and teenagers, and the positive commentary on the website, the community sincerely respects him and appreciates his work and this film. And I think it’s a great idea for the filmmakers use his personal story as a lead in to the larger discussion on archaeological ethics and Indigenous sovereignty. Unfortunately however, director Brice Habager don’t quite strike the right balance, and so end up spending too much time promoting Anderson at the expense of the larger story. A key rule in documentary filmmaking is to never turn your participants into heroes (and therefore two dimensional characters), because its undermines their credibility and distracts the audience. It really is a shame that Swift Water Place did not quite achieve that balance. Also, the equally interesting and long commitment to research into Iñupiaq folklore by his wife anthropologist Dr Wanni Anderson is set up, but never gets a pay off, so is reduced to another distracting storyline. Can we have a longer cut please?

The message of Swift Water Place is the important thing: if an archaeologist behaves respectfully and ultimately defers power to the Indigenous groups who’s culture is being studied, then the community may well support you in turn, to both stakeholders’ benefit, and that’s an important message for archaeologists and one that cannot be repeated enough. I recommend folk check out this film for themselves and make up their own mind for its effectiveness. For all my criticisms, Still Water Place still a very well made film with high production values, it balances science and ethics which is commendable, and it would make a nice centrepiece for discussion in a university classroom.